Los Angeles – Samantha Sumiko Pinedo and her grandparents enter a dimly lit room at the Japanese American National Museum, their eyes fixed on a massive book open to reveal columns of names. Pinedo’s heart races as she hopes to find her great-grandparents’ names among the thousands listed. They were among the Japanese Americans who were unjustly detained in incarceration camps during World War II.

“For many people, it may seem like a distant memory because it happened during World War II. But for me, it’s personal because I grew up with my Bompa (great-grandfather) who was in one of these camps,” Pinedo shares.

A docent at the museum gently flips through the pages of the book, called the Ireichō, and finds Kaneo Sakatani’s name near the center. Pinedo’s great-grandfather’s name is now etched in history, and his family can finally honor him.

On February 19, 1942, after the attack on Pearl Harbor and the United States’ entry into WWII, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, authorizing the incarceration of people of Japanese ancestry who were deemed a potential threat.

From the scorching heat of the Gila River center in Arizona to the freezing winters of Heart Mountain in Wyoming, Japanese Americans were forcibly removed from their homes and confined in hastily built barracks. These camps lacked basic amenities, such as insulation and privacy, and were surrounded by barbed wire. Families of up to eight were cramped into small rooms measuring only 20-by-25 feet (6-by-7.5 meters). U.S. soldiers in guard towers ensured that no one could escape.

When the 75 detention facilities on U.S. soil closed in 1946, the government published Final Accountability Rosters listing the names, sex, date of birth, and marital status of the Japanese Americans held in the ten largest camps. However, there was no clear consensus on the total number of detainees nationwide.

Duncan Ryūken Williams, the director of the Shinso Ito Center for Japanese Religions and Culture at the University of Southern California, knew that these rosters were incomplete and filled with errors. Along with a team of researchers, he took on the monumental task of identifying all the detainees and honoring them with a three-part monument called “Irei: National Monument for the WWII Japanese American Incarceration.”

“We wanted to rectify this moment in American history by acknowledging that Japanese Americans were targeted by the government. Simply having one drop of Japanese blood was enough to be considered an enemy,” Williams explains.

The inspiration for the Irei project came from stone Buddhist monuments called Ireitōs, built by detainees at camps in Manzanar, California, and Amache, Colorado, to remember and console the spirits of those who died in the camps.

The first part of the Irei monument is the Ireichō, a sacred book listing 125,284 verified names of Japanese American detainees.

“We felt it was necessary to restore dignity, individuality, and humanity to all these people. The best way to do that was to give them back their names,” Williams says.

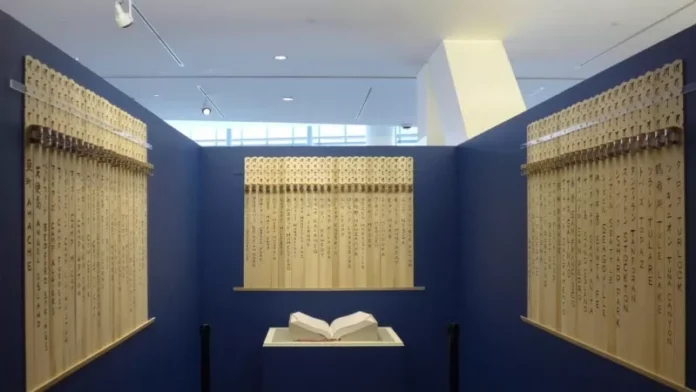

The second element, the Ireizō, is a website set to launch on Monday, the Day of Remembrance, where visitors can search for additional information about the detainees. The final part, Ireihi, is a collection of light installations at the former incarceration sites and the Japanese American National Museum.

Williams and his team spent over three years reaching out to camp survivors and their descendants, correcting misspelled names and data errors, and filling in the gaps. They analyzed records in the National Archives of detainee transfers, as well as Enemy Alien identification cards and directories created by the detainees.

“We are confident that our list is at least 99% accurate,” Williams assures.

The team arranged the names in order of age, from the oldest person who entered the camps to the last baby born there.

Williams, who is also a Buddhist priest, invited leaders from different faiths, Native American tribes, and social justice groups to attend a ceremony introducing the Ireichō to the museum.

Crowds gathered in the Little Tokyo neighborhood to witness camp survivors and descendants of detainees enter the museum, each holding a wooden pillar, called sobata, with the names of each camp. At the end of the procession, multiple faith leaders carried the massive book of names inside. Williams read